Over 170 years ago in November 1851, 143 Gaelic-speaking Nova Scotians, mostly West Highland-born, together with their seventy-one-year-old Assynt-born Presbyterian minister, Norman McLeod, set out from St Ann’s Nova Scotia for Adelaide, Australia, in a self-built vessel. After a brief dalliance with the Victorian Gold Rush, they moved on to rural New Zealand settling in Waipu in 1853. They were the first of over 800 men, women and children who were to make the same journey in self-built vessels between 1851 and 1860. Today, Waipu is a small rural town with a 2013 population of 1,671, which lies 100 kilometres north of Auckland, or 120 kilometres by road.1 The town’s rural economy is supplemented by outdoor pursuit tourism including swimming, surfing, fishing, golf, horse trekking and hiking. However, one of the town’s key tourist attractions is its museum, whose focus is the story of the migration to and settlement of Waipu. Here the Scottish origins of the settlement are writ large, reflected in the town’s strapline on the official Tourism New Zealand website; ‘Waipu is a friendly town with an intriguing history, strong Scottish heritage and spectacular natural surroundings.’2

New Zealand was colonised in 1841 and, courtesy of the New Zealand Constitution Act (1852), gained self-governing colony status just as the first of the Nova Scotians arrived in New Zealand. The Nova Scotians’ colonisation of Waipu and her sister settlements of Whangarei Heads, Leigh, Okaihau, Kamo, Whau Whau, Hukeranui and Hikurangi differed from the typical colonisation of the time. The colonial land system had been geared to individual land tenure rather than community tenure. However, ‘it is that atypicality, and the mythology that has surrounded the odyssey that has made Waipu an alluring and interesting object of study.’3 The narrative has been used as a flexible allegory for the colonial settlement of New Zealand, moving it away from a narrative of Scottish West Highland and Nova Scotian exceptionalism. In this respect the very isolation that the Gaelic-speaking colonists had hoped for has provided a visible account of Scottish migration to New Zealand in the form of the town as an artefact. In addition, the narrative has proved to be sufficiently malleable as to reflect the needs and attitudes of the changing cultural identity of the country.

This article first seeks to challenge the perceptions of the oft-told narrative of the Nova-Scotian Scots settlement of Waipu as a faith-based migration arguing that contrary to much of the existing historiography, economic and environmental concerns had an equal if not more significant impact on the Nova Scotians’ decision to migrate. Secondly, the paper addresses the nature of the nineteenth-century settlement, its engagement with Māori and its gradual incorporation within the wider colonial community. This then leads us to the twentieth-century refashioning of the story in response to both a growing tourist industry and a raised consciousness of where the town’s history fits in the context of the colonial settlement of New Zealand. This understanding has largely arisen due to the sharing and re-evaluation of the community’s origin story, led by the repurposing of the community’s artefact repository as a museum. The result is that the story is no longer one of an insular migration of a Gaelic-speaking Nova Scotian community of West Highland descent but a part of a wider New Zealand settler narrative. Furthermore, there is every likelihood that the story will continue to evolve to align itself with the demands of New Zealand society.

As the story is so closely connected with the ‘charismatic but autocratic … Rev. Norman McLeod,’ it is with him that we start.4 He was born at Stoer Point, Assynt in 1780 or thereabouts (his actual date of birth is unknown). He was the son of a local fisherman and in Nova Scotia owned a commercial fishing boat of his own. At the age of circa twenty-eight years-old, with aspirations to ordination in the Church of Scotland and with the support of the family’s minister, he had attended King’s College Aberdeen graduating in 1812 with an MA and winning the College’s Gold Medal for Moral Philosophy. He then travelled to the University of Edinburgh to complete his studies. There he fell out with the Kirk due to his fiercely Calvinist interpretation of the scriptures. The outcome of these clashes was that McLeod was denied status within the established Church. However, he remained true to his strict interpretation of Calvinist doctrine and continued lay preaching in the West Highlands. There, he continued to criticise the established Kirk and the morality of its ministry. That said, his ideology mirrored the ‘dogmatic and rigorous side’ of the character of the Free Church, which was to emerge after the Disruption of 1843.5 Employed as a teacher in the Kirk’s schools in Assynt and then Ullapool, his lay ministry drew the opprobrium of the authorities and in 1815 he was banned from any form of employment under the aegis of the established Kirk.

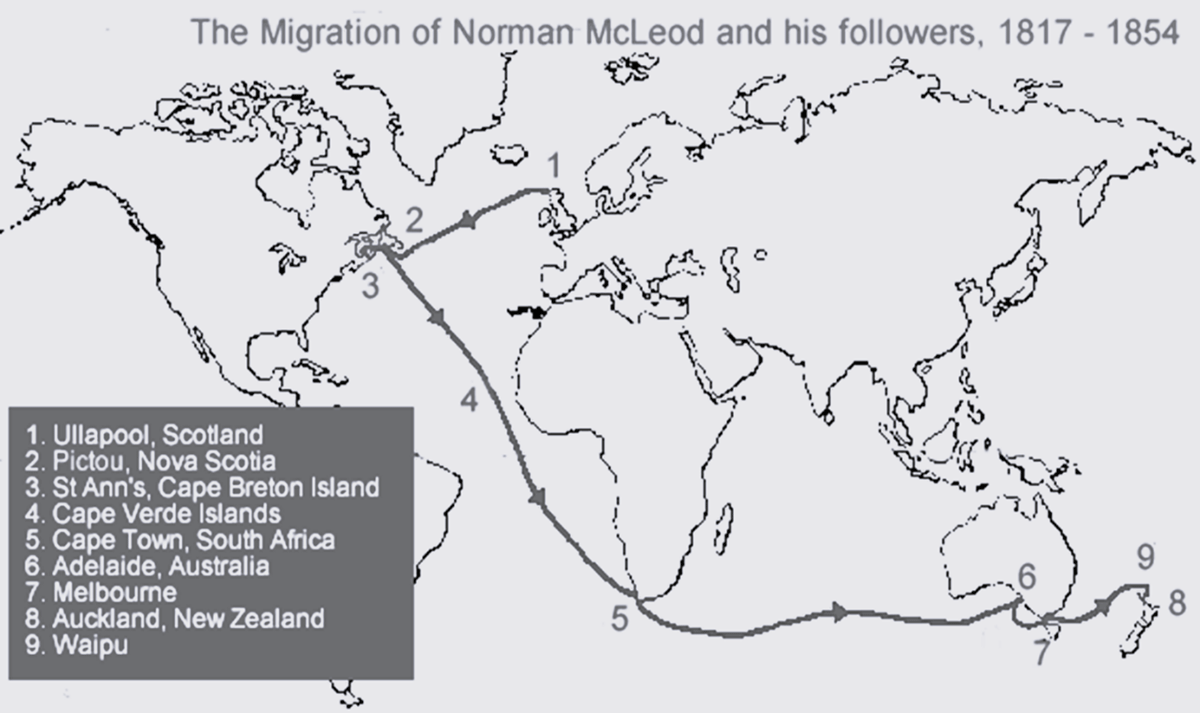

Unemployed, he was left with little alternative but to leave Scotland if he were to realise his vocation. In 1817, at the age of thirty-seven, he and his young family boarded the French barque Frances Ann at Loch Broom bound for Pictou, Nova Scotia. The barque carried some 400 Highlanders who ‘were seeking to escape economic distress’, while ‘McLeod was emigrating to escape the oppressive controls of the Church of Scotland’.6 Some of the historiography suggests that those aboard the barque were already adherents of McLeod and followed him to Nova Scotia.7 There is no evidence that McLeod was the leader of this initial migration but given the Highlanders’ origins throughout Sutherland, his reputation would have preceded him and some, especially those from Ullapool and Assynt, would have known him to be ‘a preacher of rare fame’.8 Certainly, he quickly assumed spiritual and secular leadership of the migrants on the voyage and when the barque sprang a leak in the mid-Atlantic, the lore has it that he persuaded the master to continue to Nova Scotia while marshalling the passengers to assist. The representation of this journey as a cleric-led migration is symptomatic of a wider romanticised conflation of the Nova Scotians’ migration with that of McLeod’s life. Indeed, the Waipu Museum’s website also unintentionally adds to this narrative with its map of the journey conflating McLeod’s journey with that of the Nova Scotian migrants (Figure 1).

Waipu Museum’s Map of the Journey.

Source: Waipu Museum, ‘Migration Map’, accessed 8 September 2021, https://www.waipumuseum.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/journeys_000.gif.

In Pictou McLeod’s extreme Calvinist lay-preaching was disruptive as ‘congregations splintered and the traditional churches … were thrown into a turmoil’.9 In 1820 ‘his kinfolk and converts, now known as Normanists, … built a ship, the Ark, and set out for the United States, intending to settle in Ohio.’10 However, the Ark did not get far, as a storm blew the vessel into St Ann’s Bay, Cape Breton Island, a distance of some 220 nautical miles from Pictou. Finding the land there largely uninhabited, the Normanists decided to settle and by 1829 the community appear to have been thriving and was joined by others over time. As T. C. Halliburton put it:

In St Ann’s some Scottish dissenters are the most sober, industrious and orderly settlement in the island and have a pastor of their own, endowed with magisterial authority, to whose exertions and vigilance the character of the people is not a little indebted.11

Seven years after arriving at St Ann’s, McLeod was at last formally ordained by the Genesee Presbytery in New York State. The main targets of McLeod’s sermons were consistently the Church of Scotland, landlords and sinners. The title of his 1843 book, amply highlights his distaste of the Kirk, The Present Church of Scotland and a Tint of Normanism Contending in a Dialogue, as does its contending dialogue: ‘I should at once prefer being chained to the West India slave, enjoying full liberty of conscience, to being joined with the Scottish clergy in all their enjoyment under the present power of their disposition and the actual spirit of their administration.’12

However, three decades after settling in St Ann’s, McLeod was in danger of losing his grip on his congregation. The 1843 Disruption had effectively seen to his criticisms of the Church of Scotland, while the St Ann’s settlers, including McLeod, had left their landlords in Scotland and now owned their own land, only leaving the sinners as targets. In the latter half of the 1840s this was often his secular nemesis and the community’s elected representative to the Nova Scotian House of Assembly, John Munro. Munro had been one of the crew aboard the Ark on its voyage from Pictou to St Ann’s and hailed from Assynt where he had been a tenant farmer. In St Ann’s, Munro had become a successful businessman, a boat-builder and owner, a trader and the owner of the community’s store. However, McLeod had ‘engaged in bitter feuds with all of the strong men in the community,’ and in 1847 McLeod accused Munro of smuggling brandy from the nearby French Islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon.13 He even had excise officers board Munro’s ships. This feud played out in the local newspaper with Munro striking back by levelling similar charges against McLeod’s sons, in a chain of accusation and counteraccusation.

From his pulpit, McLeod escalated the feud by calling for a boycott of Munro’s businesses, which was to have dire consequences in the winter of 1849. In 1848 one of the community’s core income streams, the fisheries, failed as did the harvest due to potato blight and wheat rust. In 1849, the harvests failed again, while the fisheries remained under intense pressure from competing American fishermen. With food and work in short supply, McLeod’s boycott of Munro’s businesses meant that his stricter adherents could not raise cash by selling their timber to Munro and were thus unable to earn the money to feed themselves from Munro’s stores which were similarly proscribed. McLeod instead resorted to ‘writing letters to the government, calling on them to bring in provisions.’14 While the harvests were better in 1850, Cape Breton now found itself in the grip of an economic depression and unsurprisingly the community was ripe for migration on economic and environmental grounds. Significantly, this depression was to continue until 1858, and with the return to economic health, migration journeys ceased in 1859.

During the hardships of the late 1840s, McLeod received glowing reports of Australia from his son, Donald, whose letter appears to have circulated widely amongst the community. McLeod comments in 1849 that the letter ‘is seldom in the house; for its information is so interesting … that it is already in half tatters, by frequent perusal, from place to place.’15 When combined with the community’s environmental and economic hardships, the letter was the catalyst for migration, although McLeod’s role in the decision to move is unclear. In a history commissioned by the Waipu community in 1947, N. R. McKenzie comments that at first, McLeod ‘was little more than an interested spectator to his people’s excitement’.16 This position is supported by Maureen Molloy who, drawing on McLeod’s letters, comments that there is not ‘any evidence that he led the emigration.’17 Indeed, in 1849 McLeod observed that there was ‘a good degree of excitement among my own friends here’ and that he was having to dampen the enthusiasm of his own family, of whom he wrote that ‘some would choose to be near their … brother …. But I insist on their patience.’18

Laurie Stanley suggests that McLeod’s motives may have been millenarian.19 Certainly his purported 1866 death bed exhortation to his adherents; ‘children, look to yourselves. The world is mad!’ would suggest that this was a central theme for him.20 It would appear from his own correspondence that his decision to go was driven by a search for religious freedom, although, given that he had effective confessional control in St Ann’s this may speak more to his fear of losing the leadership of his congregation.21 That said, the main causes for the Nova Scotians’ migration were economic and environmental, and there is no evidence that those who emigrated did so due to a profound sense of religious belief or adherence to McLeod’s teachings.

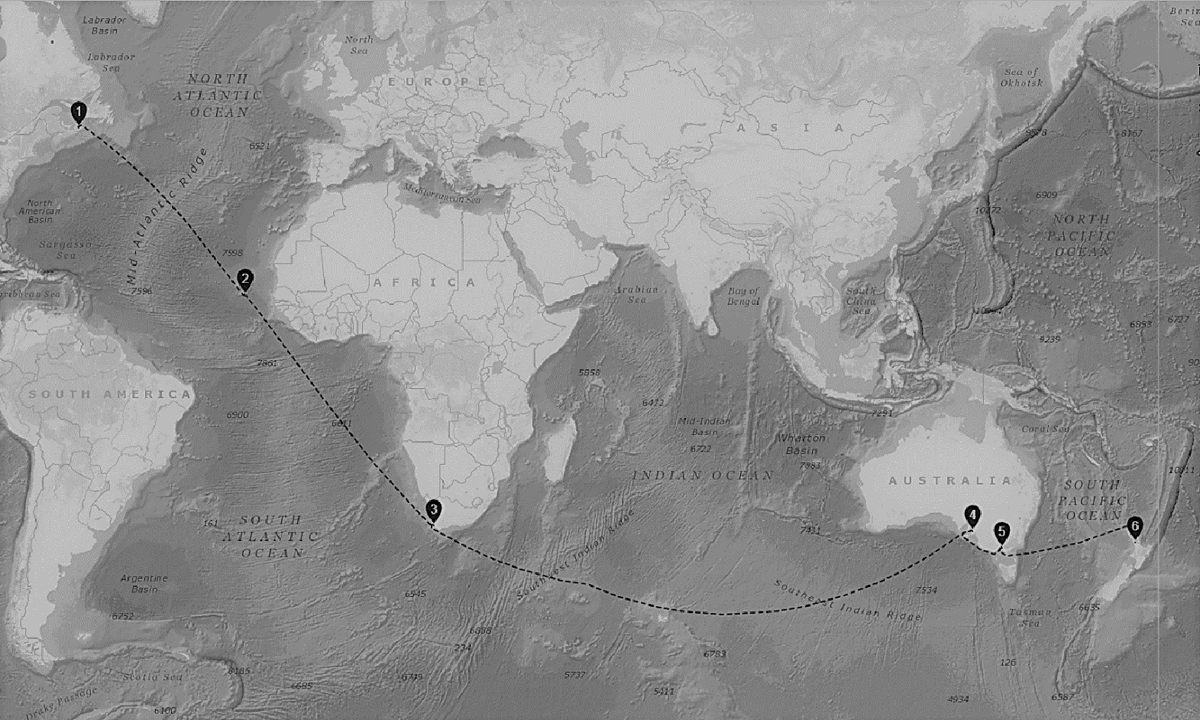

The migrants constructed their own ocean-going ships and the first of these, the Margaret, with the septuagenarian McLeod and 139 others on board, left St Ann’s bound for Adelaide in October 1851. They resupplied themselves enroute in the Cape Verde Islands and Cape Town, arriving in April 1852, a journey of some 12,000 nautical miles (Figure 2).

They had thought that they had been followed by 136 others aboard the Highland Lassie, however she was ice-bound in St Ann’s harbour and did not depart until May the following year, arriving in Adelaide in October 1852. There, the Nova Scotians found themselves in an Australia gripped by the Victorian Gold Rush and the migrants made their way to Melbourne where they encountered dreadful conditions. Living in tents on the banks of the River Yarra, they found no land to settle and a venal society, where murder and robbery were commonplace. They were also visited by typhoid, which was no respecter of piety, and McLeod lost three of his six surviving sons to the fever. This was not the paradise that had been promised in Donald McLeod’s letter. The older migrants, who spoke no English, more than ever, wanted a land where they could continue their devotions and speak in their mother tongue. So, the decision was made to journey on to the newly colonised islands of New Zealand.

Australia had exacted a toll and of the 276 to reach Adelaide in the first two ships, only 123 made the initial journey to Auckland in September 1853, although many were to follow, some with gold in their pockets. Nor did their arrival go unnoticed in the New Zealand media, with the Daily Southern Cross reporting:

The Gazelle brings us an addition of hardy and enterprising immigrants (originally from Ross and Sutherland shires), who migrated first to Nova Scotia, and thence to Adelaide, where they have sojourned for the last twelve months. We believe they are all more or less conversant with every branch of agricultural industry, as well as with that knowledge of practical colonization for which the backwoodsmen … of Nova Scotia, are so deservedly famous. They have been drawn towards New Zealand by an assurance of its agricultural, pastoral and great maritime capabilities; and, as upon their report will mainly depend [on] a further influx of the same valuable class of colonists.22

Significantly, there was no mention of the migrants’ religious leader and McLeod was not amongst the initial 123, having remained behind to shepherd the others to Auckland later that year. Nor was McLeod involved in the negotiations with Governor Grey and his successor Colonel Wynyard for the grant of land at Waipu and Ruakaka, which were first settled in September 1854. The land was well wooded and fertile and the only drawback for the settlers was that it did not have a natural harbour for their shipbuilding.

However, they were pleased with the land and the news made its way back to Nova Scotia, establishing a chain of migration on a further four self-built vessels. Pointedly, it was not until this news arrived that migration recommenced. The Gertrude arrived in New Zealand in December 1856 with 176 settlers. Her owner was McLeod’s nemesis, John Munro. His political aspirations had been curtailed by defeat in Victoria County’s (Nova Scotia) 1854 elections when he lost his seat and this seems to have been the catalyst for his migration, not confessional adherence. The Gertrude was followed by the Spray in 1857 with ninety-six settlers, the Breadalbane with 160 in 1858 and in 1860 the last of the ships, the Ellen Lewis, which was part-owned by John Munro’s son, John Munro Jr, with 235 migrants. In all, more than 800 men, women and children made the journey to Waipu.

The scholarly historiography surrounding the migration is largely subsumed by McLeod’s persona, and sociologist Maureen Molloy argues that this historiography demonstrates ‘a clear dichotomy between those written by members of the community and those written by “outsiders”.’ Outsiders, she claims, are overly-focused on McLeod, depicting him as ‘“autocratic”, a “demagogue”, a “feudal laird”, “cruel”, “vindictive”, “horribly attracted to women” and “unable to love”’ and by implication portraying ‘his parishioners and fellow migrants [as] docile, gullible and unthinking.’23 In contrast, she contends that the accounts of community insiders focus ‘more on the lives, attitudes and actions of the ordinary settlers,’ adding that while they give ‘great weight’ to McLeod’s religious and moral leadership, ‘they do not leave much impression of docility, lack of humour or gullibility’.24 Even Stanley, as stern a critic as any of the outsiders, acknowledges that historians have been harsh towards McLeod commenting that he ‘was not a religious crank. He was very much a product of his age.’25 This theme is common to both outsiders and insiders. However, insider histories are not so driven by the idea of McLeod as an overarching religious aberration, rather they are more focused on the migration and the founding of their community, in which McLeod plays an important but not exclusive role.26 Outsiders have been apt to over-emphasise McLeod’s control over his community. For instance, Michael Fry says of him that ‘when he resolved that, staring starvation in the face, they should all go to Australia, to Australia they went.’27

McLeod’s role in the decision was not as definitive as Fry suggests and such narratives ascribe an almost messianic aura to him when he was more of a schismatic and one whose teachings were compatible with those of the Free Church of Scotland in 1843. Furthermore, such narratives deny the Nova Scotians agency or participation in the decision-making process. They overlook the stories of those non-adherents like John Munro who were also prepared to travel South, notwithstanding the risk of McLeod’s putative influence. Nova Scotian descendant, Neil Robinson, comments of the non-adherents that between ‘them and the minister there existed a state of armed neutrality. They went to New Zealand because they felt that, in this community whose ways they knew, there was a better chance for their families’ welfare; but they objected to the minister’s rigid control of their private life.’28 Robinson also makes the point that the majority aboard the Breadalbane were from the Nova Scotian island of Boularderie, whose minister had opposed McLeod, and they were not Normanists.29

That such opposition existed is ample evidence that the reasons for their migration were more diverse than blind faith in a charismatic spiritual leader. As Molloy says, ‘although there may have been some people who left Cape Breton to follow Norman McLeod, the principal reasons for migrating were economic.’30 The evidence supports this and while much of the outsider historiography seeks to label this a faith migration led by a charismatic and forceful religious leader, this was not the case. Even in Waipu, McLeod appears to have divided opinion and, in any event, not all could have attended his services as McLeod’s church only had room for a congregation of 200, a far cry from the 1,200 that his St Ann’s church held. Nor, however, can he be dismissed as an irrelevance. His family were one of the catalysts for migration and he did have a fanatical following. For instance, when he died in 1866, aged circa eighty-six, local lore has it that his adherents dismantled his church and burnt his pulpit so that no other could preach from it. Indeed, it was not until 1871 that the new church was completed and a minister from the Auckland Presbytery installed.

The notion of this having been a cleric-led migration is not without precedent. Many of the migrants aboard the Margaret were likely to have been firm McLeod adherents, although this is unlikely to have held true for the Highland Lassie, whose owners, the McKenzie brothers, ‘were probably not Normanists … [and had] stronger links with the people from [non-Normanist] Boularderie.’31 However, cleric-led migrations were not unusual at the time, as McLeod and his followers’ own journey from Pictou to St Ann’s in 1820 attests. Other examples include the recruiting of 4,000 Highlanders for New South Wales under the Presbyterian cleric John Dunmore Lang’s Bounty Scheme from 1837–41. New Zealand itself had experienced confession-led migrations prior to the Nova Scotians’ arrival, for example the Otago Association’s settlement of Dunedin in 1848. That settlement’s lay leader, William Cargill, ‘compared the Otago pioneers to the pilgrim fathers.’32 Its minister, Thomas Burns, wanted ‘to establish a Free Church theocracy.’33 However, not all the colonists shared their leaders’ enthusiasm for a Free Kirk theocracy, with the 1851 religious census of Otago identifying that only 30 per cent of the population attended either the Free Church or the Church of Scotland and that the churches shared that attendance equally.34

Meanwhile in Canterbury, two years later, the first of four Canterbury Association ships arrived and by 1853 the number of migrants exceeded 3,500. This was an Anglican-led migration and, emulating Burns’ aspirations, the Canterbury Association espoused confessional exclusivity: ‘We intend to form a Settlement, to be composed entirely of members of our own church, accompanied by an adequate supply of clergy, with all the appliances requisite for carrying out her discipline and ordinances.’35 Similar to Cargill’s sentiments, the Association encouraged the allusion to the Pilgrim Fathers with the settlers dubbed the Canterbury Pilgrims prior to their departure. However, as with Otago, confessional exclusivity proved difficult to achieve and the number of migrants enlisted fell short of the required numbers prior to sailing, prompting the recruiters to relax the regulations and Anglican exclusivity was diluted with each sailing.36 The theocratic aspirations of both the Otago and Canterbury settlements were further attenuated by an influx of immigrants with the discovery of gold deposits firstly in the Aorere Valley in 1856, then the more substantial finds in central Otago in 1861 and the West Coast goldfields in 1863. Conversely, without mineral deposits and substantially isolated from the rest of colonial New Zealand, Waipu remained a largely insular settlement, whereas even other ethno-centric led settlements such as those of the Scandinavians at Norsewood and Dannevirke, were quickly incorporated into the colonial mainstream. Again, the atypicality of the Waipu migration lends itself to a cohesive if romanticised narrative.

In the early years the community largely kept to itself. The Normanists’ aspirations had been to found a godly Gaelic-speaking society based on McLeod’s ideology, while the non-adherents were keen to make an economic success of their fresh start in New Zealand as a Gaelic-speaking community. Adherents and non-adherents alike were isolated by language and culture and Maureen Molloy’s 1986 article, ‘No Inclination to Mix with Strangers’, neatly encapsulates the Nova Scotians’ attitudes towards outsiders. Her research shows that amongst the settler generation marriage patterns ‘within the groups tended to be of two forms: cousin marriage and sibling exchange marriage.’37 Compounding this insularity was the limited and difficult land transport links with the only real access for bulk transportation being the sea, from Marsden Point and Lang’s Beach, where coastal vessels had to stand off and load and unload to/from smaller boats. Yet, the community were quick to clear land, plant crops and get them to market. Their efforts and sense of community, recognised in the national media;

From one person alone, in the town of Auckland, … [Waipu’s farmers] have received £800 this year for wheat (how much from others we have no present means of ascertaining,) and that wheat described by the buyer as the best in the country. The quality is attributable to the unity of feeling which prevails among the Nova Scotians, enabling them, through neighbourly assistance, to cut their corn as soon as ripe, and to stow it away at once.38

Connection to the wider colonial community was a slow process that started with the community’s schools. Despite migrating as a Gaelic-speaking community, the school curriculum was conducted in English from the beginning and from 1857 outsiders began to replace settlers as teachers. By 1862 five schools had opened, all staffed by government registered and licensed teachers. This altered the isolationist dynamic with children being raised as bilingual, and the use of Gaelic eroded. Economically, the early settlement struggled, as without effective transportation links it was difficult to get surplus agricultural produce to market, especially livestock. Initially, contact with the wider colonial community was as limited as the transport links. This changed with the completion of the post and telegraph office in 1875 and the remainder of the century saw a slow build-up of outsiders in the community, which also began to reap the benefits from improved land transport links. From 1876 monthly or bi-monthly English reports of mundane Waipu life began appearing in the Auckland based national newspaper, the New Zealand Herald in a section entitled Country News.39 Increased contact with English-speaking New Zealand, the English-language school curriculum, the need to engage with colonial bureaucracy and non-Gaelic-speaking incomers all contributed to an erosion of Gaelic-speaking culture. By the time of the publication of the settlement’s first history in 1928, written by the Gaelic-speaking Gordon MacDonald, Gaelic was on the wane and MacDonald bemoaned that; ‘in another generation or two the Gaelic language will have disappeared.’40

Missing from much of this narrative and the historiography, is the settlers’ interaction and relationship with Māori. In their submission to the Waitangi Tribunal in 2013, the local Patuharakeke hapū (Māori clan, equivalent to a Scottish sept) noted that,

there are twenty-four recorded defensive pa [hillforts] in and around Waipu. Te Paritu is one at which tupuna [ancestors] of Patuharakeke were massacred by Ngati Whatua. This event in our history was recorded in a small but significant note in Deeds Relative to the Extinguishment of Native Title around 1857. Te Pirihi and his cousins claimed some compensation for relatives massacred on the ground, due to the Nova Scotian people taking over the area. Patuharakeke have kept well away from what became a very tapu [taboo] area.41

There is good evidence of pa building along the coast from Whangarei to Pakiri.42 George MacDonald’s 1928 history says that the ‘settlement was surrounded by Māori villages’.43 Yet, from Takahiwai to Pakiri, a coastline of some eighty to ninety kilometres, there are no Marae (the Māori enclosure containing a wharenui [meeting house]). The Patuharakeke maintain that the sale of the 40,000 acres at Waipu and 14,800 acres at Ruakaku by the Crown left ‘not one single acre of these two blocks … in Māori ownership, and so the Patuharakeke were relegated to living just at Takahiwai from the 1850s.’ And that this ‘is why the marae at Takahiwai is the only one from the South side of the Whangarei Harbour all the way to Pakiri – because the Crown left no land for Māori in that whole coastal strip.’44 Indeed, John Munro Jr (the son of John Munro and the part owner of the Ellen Lewis) in his letters to the Nova Scotian Gaelic language bi-weekly, Mac-Talla between 1894 and 1902, wrote often about interaction with Māori and Māori culture.45 In one letter he demonstrates an understanding of the iniquity of Māori land sales, commenting that,

Land courts are appointed, headed by judges who are knowledgeable about the customs and genealogy of the Maori ancestors. These courts sit from time to time when land is to be sold, and many attend. Not a turf of soil is sold until they all agree. Lawyers attend the courts to defend the rights of the Maori, but when they get their share of the proceeds, very little goes to the Maori.46

However, in interviews with descendants the common responses were that there were no Māori in Waipu when the Nova Scotians arrived, or that Māori had welcomed and shared life skills with the settlers. These narratives are mirrored in the town’s Grand Pageant whose narrator comments that ‘by 1826 when D’Urville passed through, the area was completely uninhabited.’47 This terra nullius narrative or rationalisation is not uncommon in New Zealand, or for that matter amongst other European settler colonies. However, the Pageant also recognises that there were Māori in the vicinity, but further North, and it emphasises a commonality of values between Māori and Highlanders:

Māori came down from the Takahiwai and showed them how to make shelters using raupo, and traded produce with them. They got on well with the Māori people. They both valued family and community highly. The need to help each other was engrained in their nature.48

Another narrative offered in interviews to explain the absence of Māori was that the land was tapu (taboo) which, as noted in the Patuharakeke’s submission, it was. Whatever the real reasons were, these perceptions represent a gap in the story that would benefit from further investigation. Significantly, the Nova Scotians did not encounter the levels of conflict with Māori that other parts of the country experienced as by the time of their arrival, Hōne Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti had agreed peace terms with the colonial government (1846) and Northland’s wars were over. Further south in the Taranaki, Waikato and the Bay of Plenty insurrection against colonial rule continued until 1872. It is not unreasonable to suggest that this, together with declining nineteenth century Māori numbers, which fell from c.80,000 in 1840 to c.42,000 in 1896 may have fed into descendants’ perceptions.49

That said, there was a Scottish flavour to the Waipu land transaction. The land had been part of a 100,000-acre block purchased by the Edinburgh-born British Resident, James Busby, in 1839 for the sum of forty pounds just six weeks before the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi (6 February 1840). Busby had been British Resident from 1833, but in 1839 his position was eroded by the appointment of Captain William Hobson RN as Lieutenant Governor. Given that he was one of the treaty’s draftsmen, he was more than aware of the Crown’s plans to stop Māori from selling land to anyone except the Crown once the Treaty was signed. Following what was probably New Zealand’s earliest case of insider trading, the Crown invalidated the purchase in 1841, although Busby ran up considerable debts seeking compensation. Briefly, the land was returned to Māori but was repurchased, this time by the Crown, in 1853 and 1854 for two pence per acre for Waipu and six pence per acre for Ruakaka. The land was then sold on to the settlers for ten shillings per acre, a substantial profit for the Crown. The Crown Purchaser was a Scot, John Grant Johnson and he reported to the Chief Land Purchase Commissioner, another Scot, Donald MacLean, who in contrast to the racism of many settlers respected Māori cultural traditions and importantly, spoke Māori. Alan Ward says of him that his ‘early acquisitions showed care to gain the consent of hapū in open dealings’, although by the late 1850s he had developed some dubious practices, which ‘provoked mounting tension and finally physical conflict between sellers and non-sellers.’50

The son of a Highland tacksman from Sutherland, MacLean spoke Gaelic, and had been raised by his grandfather, a Presbyterian minister. He had been destined for Presbyterian ministry himself and held strong Calvinist beliefs. Waipu’s communal land transaction was atypical, as the colonial land system was geared to individual land tenure. MacLean’s heritage and faith may have contributed to the outcome, and he was likely persuaded by their petition as he was instrumental in drafting the 1858 Auckland Waste Lands Act legalising such a settlement retrospectively. This was proposed in a Provincial Council Meeting in an address that was likely penned or edited by MacLean and specifically references the Nova Scotians:

A provision is also proposed to be made by which blocks of land may be set apart for special settlement … This plan of settlement is not new, although it is now for the first time to be legalised here. Already an experiment on this mode of colonisation has been tried with success in the Wangerei [sic] district by immigrants from Nova Scotia amongst whom the beneficial effects of unity of purpose, mutual support and hearty co-operation, in overcoming the difficulties incident to new settlement have been strikingly developed.51

The Waitangi Tribunal created by the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 to determine whether Crown actions or omissions were/are in breach of the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi has continued to evolve, ‘adapting to the demands of claimants, government and public.’52 In addition the Act has resulted in a public discussion that has challenged the accepted view of a benevolent treaty history and good Crown–Māori relations. New Zealand society and attitudes toward Māori have experienced a fundamental change since the formation of the Waitangi Tribunal. Nor has Waipu remained isolated from this sometimes uncomfortable discussion and while the story of the community’s relationship with local Māori bears further investigation, steps are being taken to redress this. In a 2014 interview, Patsy Montgomery, the Manager of the Waipu Museum, recognised that the omission of the Māori story was a ‘most significant one’ and commented that a Māori representative had joined the Museum’s Board of Trustees.53 Reflecting this omission, the Museum’s 2021 Strategic Plan has targeted the following amongst a number of other planned goals:

Increase the awareness of Te Tiriti o Waitangi [The Waitangi Treaty] and how it relates to governance, the acquisition, display and research of taonga [property] within the Waipu Museum.

Liaise with Mana Whenua Patuharakeke to develop an appropriate space for their story as it relates to the Nova Scotian settlers.

Add value to the collection through comprehensive research and the acquisition of objects of significance and relevance to the Nova Scotians, their descendants and Mana Whenua Patuharakeke.54

The revisiting of the town’s interaction with Māori is one of the more recent initiatives in the twentieth and twenty-first century refashioning of the story in response to a growing and changing understanding of New Zealand’s colonial past, the rise of family history and genealogy research and a burgeoning tourist industry. The origins of the adaptation of the story have their genesis in the community’s Golden Jubilee celebrations of February 1903. This was an exclusively Nova Scotian (or Novie) gathering of the descendants, including some of the surviving original settlers, but here there is a first hint of the community’s story becoming one of national relevance in the opening sentence of the New Zealand Herald’s report of the 1903 gathering:

The chief feature of the Auckland Weekly News … is a series of photographs … of the jubilee celebrations at Waipu. The function, which is an event of historical interest to New Zealanders, took the form of a gathering of the clans, and hundreds of the original settlers and their descendants foregathered at the Nova Scotian settlement to take part in celebrating the important occasion.55

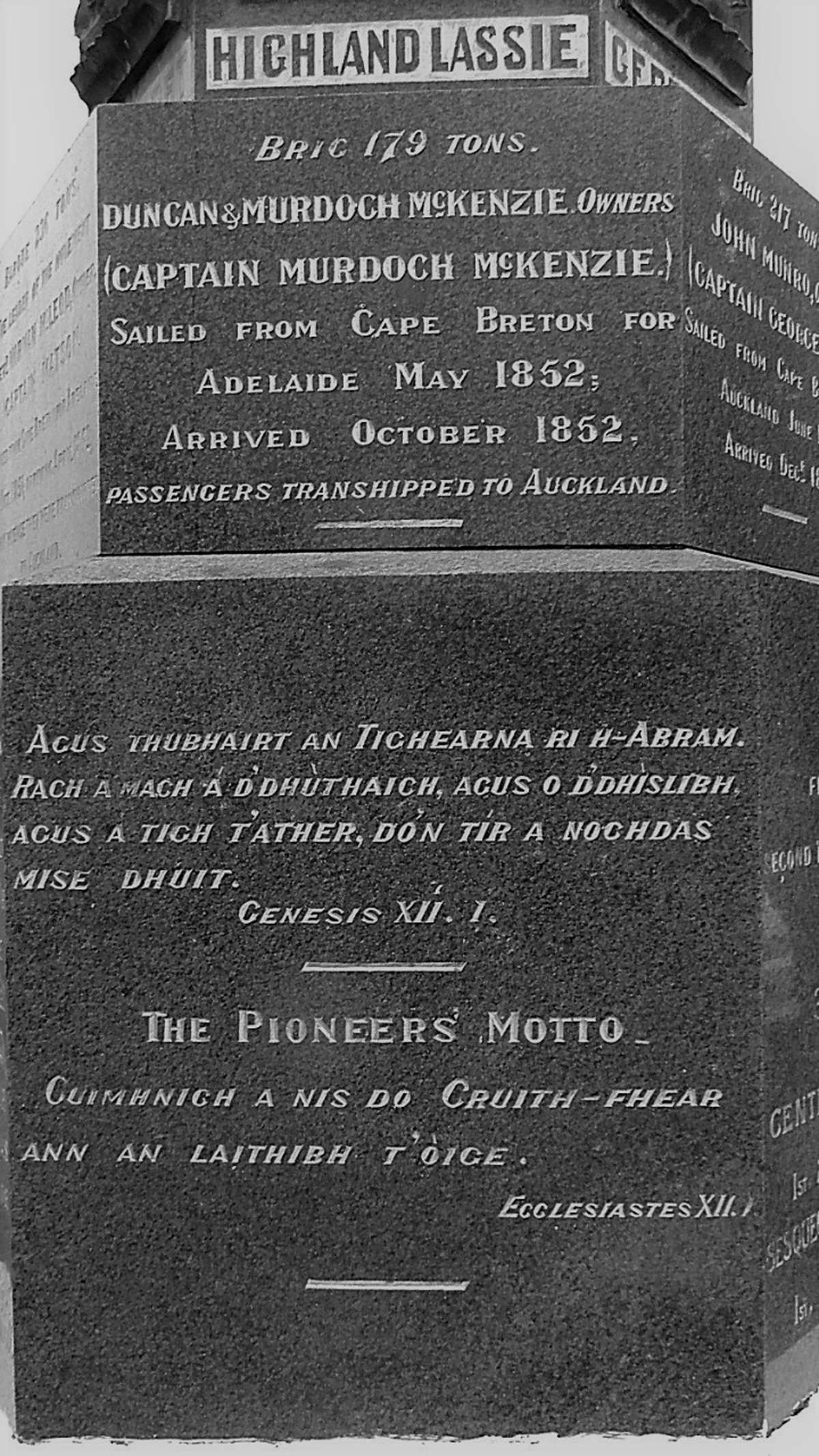

Prior to the beginning of the First World War a further two gatherings were held, the School Reunion (1907) and the Diamond Jubilee (1914) and like the 1903 Reunion these were for Novies exclusively. As Molloy notes, these gatherings served to ‘remind both the ‘Novies’ and the ‘foreigners’ of the boundaries between the two’ (Novies being how those of Nova Scotian descent sometimes refer to themselves).56 The 1914 Diamond Jubilee also saw the unveiling of the Settlers’ Monument (Figure 3).

An interesting feature of the monument is that it is also testament to the erosion of the Gaelic language and possibly Gaelic culture amongst the town’s inhabitants. As at its base, the monument names the six migrant ships, their masters and owners, but pointedly only one of the twelve panels is in Gaelic (Figure 4).

Gaelic Panel at the Base of the Settlers’ Monument.

Source: Iain Watson, 10 December 2014. (Translation; ‘Now the Lord had said unto Abram, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto a land that I will shew thee:’57 and the Pioneer’s Motto; ‘Remember now thy Creator in the Days of thy Youth’.58)

These gatherings and the Monument’s construction mark the beginning of the community’s physical self-promotion of their story, albeit initially introspectively. However, there was a hiatus in this self-promotion until after the Second World War apart from the unveiling of the community’s War Memorial in 1919. This was a less Novie-centric memorialisation and says more about the town’s engagement with wider New Zealand society. The Waipu Caledonian Society’s roll of honour lists ninety-one members and ex-members of the society, including two women, who had served during the Great War.59 MacDonald says that ‘Three hundred and twenty men and three trained nurses heard the call.’60 Given that the 1911 population of the Waipu Riding was just 1,017 of which 545 were males, MacDonald’s numbers may include those from Waipu’s sister settlements.61 Whatever the accuracy of the numbers, they do show the community had become more engaged with wider Dominion society by this time.

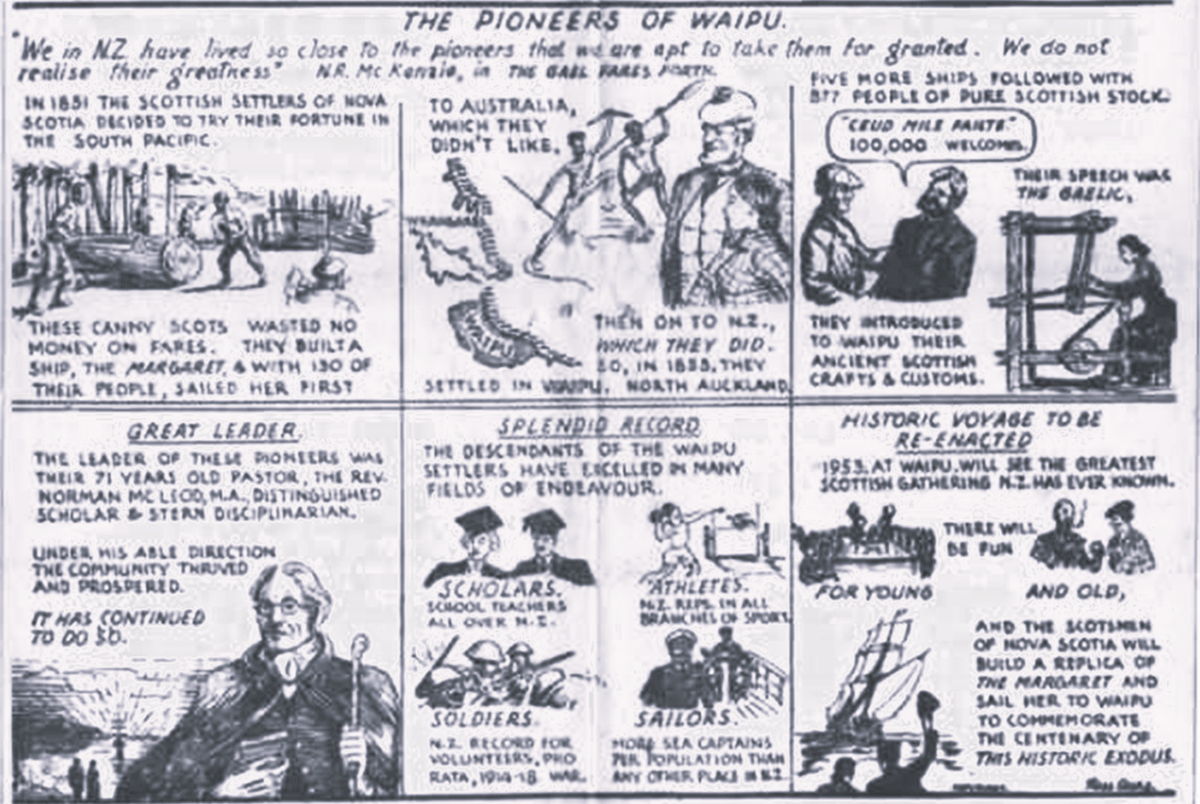

In 1953, the community, still largely of Nova Scotian descent, sought to celebrate the centenary of their settlement of Waipu. They chose to do so by re-enacting the story in a pageant and by building the forerunner of today’s Museum, then dubbed the House of Memories. Their engagement with these undertakings were still Novie-centric, and largely an act of community celebration, commemorating the achievements of their pioneering forebears. However, the 1953 centenary appears to have prompted the community to publicise the story more widely. The Pageant was advertised to a national audience, appealing to the wider settler community with the strap-line, The Pioneers of Waipu (Figure 5).

Advertisement for the Waipu Grand Pageant, 1953.

Source: ‘160th Anniversary of the Arrival of the First Waipu Settlers – The Settler’s Arrival is Re-Enacted at the 1953 Celebrations”, Clan Matheson – New Zealand website, accessed December 2014, http://www.clanmatheson.org.nz/blog/category/history/waipu-migration/.

In addition, only descendants of the original settlers were involved with the building of the House of Memories. Furthermore, there is little to suggest that the House was intended as much more than a community repository and local archive. As Patsy Montgomery comments, the descendants ‘probably at that stage appreciated what their forebears had achieved and were well aware that if they didn’t do something a hundred years down the track, … things would dissipate.’62

Despite the financial and human capital invested in the building of the House of Memories, it would appear that community interest subsided and the House, more often than not was closed. Patsy Montgomery describes it as ‘a classical spider factory … granny’s attic, museum, which was very fascinating but wasn’t really looking after the … collection.’63 In 1979, Betty Powell, a retiree from her family farm in the adjacent countryside, is said to have commented that ‘she didn’t like coming to a town where the museum was closed,’ and was promptly co-opted to become involved in the House despite not being a descendant herself.64 As a result, by 1981 the House had been resurrected as a museum with the input of non-descendants, and this is where Waipu stole a march on the modern-day phenomena of roots tourism, family histories and genealogy research. Powell was first and foremost an amateur genealogist and appears to have worked tirelessly to make sense of the documents stored in the House. Even today, genealogy continues to have a key role in the Museum’s activities, with the genealogists’ offices and records located within the museum and their services advertised on the museum’s website. From Powell’s handwritten ledgers that started with the 800 settlers on the six ships and with the benefit of technology, the database has expanded to more than 100,000 names. However, its 1981 resurrection as a Museum was still limited in scope and it was ‘neither a granny’s attic museum with all its charm and quaintness … nor was it a modern storytelling museum’ and ‘so didn’t capture the potential power of the story.’65

The modern museum has its genesis in the town’s decision to reprise the pageant for the 2003 sesquicentennial. The director, a Nova Scotian descendant, Lachlan McLean wanted the story ‘to be well … researched.’66 In addition to his own research, he drew on that of documentary makers John and Karen Bates.67 The research highlighted that there was a need to revisit the Museum’s role in telling the community’s story moving it away from a dusty collection of artefacts to a modern museum and dovetailing the narrative with that of the Pageant, as ‘people [in the community] recognised the story was really important.’68 As with the differences in the historiography this story fits the community narrative and as with the insider histories, Norman McLeod’s presence is acknowledged, but does not overwhelm the narrative. Here the co-operative ethos of the community is central to the museum’s ‘exhibition, [which] is about co-operation and people [visitors] get it,’ even if the message is not overtly stated in the displays. This fits with the pageant’s messaging as a ‘universal story of hope, resurrection and possibility.’69

The Museum’s messaging supports Pākehā New Zealanders’ notions of a pioneering frontier culture, although it also reflects the community’s willingness to engage with post-colonial New Zealand. As Tanja Bueltmann notes, the Scottish experience in New Zealand has all too often been ‘obscured by popular and anecdotal histories.’70 In part the Museum also fosters this through, for instance, its Highland Clearances display. This theme is also incorporated in the town’s pageant. While MacDonald vaguely suggests that ‘McLeod and his people were probably amongst those who suffered,’ McKenzie states that neither McLeod nor his followers were ‘involved in the “Clearances”.’71 There is no evidence that any of the settlers were victims of the clearances, and this is supported by descendant interviews. The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand notes that the Scots who migrated to New Zealand ‘were not refugees from the Highland Clearances, but they were of modest means, typically farmers and artisans such as weavers, and later tradespeople and skilled workers. They left harsh economic times for a better life.’72 Indeed, the majority were Lowland Scots, and yet, the Clearances victim migration myth remains resilient in New Zealand despite the evidence.73

In a similar vein this Highlandist lore is enhanced by the town’s Caledonian Society, which has held Highland Games every New Year from 1871 (apart from the pandemic years of 2021 and 2022) and remains a leading light in the waning Highland Games movement. However, the annual games have little to do with the Nova Scotians and their story but everything to do with the use of Highlandist iconography in New Zealand. Indeed, there is no evidence of the settlers having brought any tartan with them, and the clothing amongst the settlers’ artefacts in the Waipu Museum is largely monochrome. In addition, dancing, music, and drinking were forbidden amongst the Normanists, while non-Normanists were expected to respect these strictures, without necessarily complying. Worthy of comment is that in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, Scots accounted for up to 24 per cent of white New Zealand and nowhere outside Scotland was the concentration of Scots as high.74 Even though Caledonian societies are now on the decline, Highlandist iconographies and narratives continue to find resonance within New Zealand. Combining this with the tale of Waipu’s atypical settlement the story has ‘entrenched misunderstandings of the character and settlement of Scottish migrants in New Zealand.’75 None of which is deliberate on the part of the town itself, rather the pliability of the story feeds wider perceptions of a pioneer past, and visitors are able to take what they want from the story. In this respect, Waipu, its Caledonian Society and to a lesser extent, the Museum, are reacting to the demands of a society in which many can trace their ancestry to a Scottish settler. The question is whether this is a vestigial legacy of the Caledonian Societies traditional role as sites of memory, or whether there have been changes in the nature of Scottish associationalism with sites of memory now including the growth in genealogical research and family histories.

The pliability of the atypical Waipu migration has been a core theme throughout this article and starts with the interpretations of the migration as a faith migration rather than an economic and environmental one. While faith was important, by the 1850s McLeod’s confessional position had been normalised by the Disruption and in St Anne’s his ministry was not that of a persecuted minority. Nor did he lead the migration although, for the community faced with economic and environmental hardship, he and his family provided the focus for migration to the Southern Hemisphere in the form of Donald McLeod’s letter. The story holds different interpretations for descendants and outsiders. This is in part due to limited scholarly research resulting in only three histories having been written about the migration and settlement of Waipu: MacDonald’s sometimes fanciful The Highlanders of Waipu (1928), N. R. MacKenzie’s, The Gael Fares Forth (1935) and Neil Robinson’s, To the Ends of the Earth (1997). All were amateur historians, MacDonald was a Gaelic-speaking outsider from Dunedin, while both MacKenzie (a school teacher) and Robinson (a journalist) were descendants. Sociologist Maureen Molloy’s book, Those Who Speak to the Heart (1991), does address the migration but its primary focus is the practice of kinship in a Highland Scots community in nineteenth-century New Zealand. It discusses the formation of intensely inter-related kin groups, which provided a source of material and emotional support for immigrants facing dislocation during the settlement of Waipu. The legacy of these atypical kin groups has provided the town with a cultural longevity that other European settlements, such as the Scandinavians in Dannevirke and Norsewood, the Scots in Dunedin and the Anglicans in Christchurch, have been only able to access tangentially due to their early dilution by other settlers. Yet without a more definitive and more fully researched history of the settlement, the story will continue to be open to interpretation and revision in line with contemporary influences and needs.

Despite McLeod’s shadow and his centrality to the migration story, religion is not the legacy of the migration. The settlers did not seek to proselytise their beliefs, to any extent, outside their community, nor did all the community and much of the next generation adhere to McLeod’s strict Calvinist doctrines. Part of the legacy lies in the promotion of a form of Highlandism, but that was not necessarily a culture that came with the Nova Scotians. Ironically, its promotion says more about Waipu’s inclusion into colonial society, being derived from an undercurrent of Highlandism within New Zealand society, rather than West Highland culture. More significantly its legacy lies in the sharing of its malleable migration story. As regards that story, the Scottish migration theme is only a part of the narrative and its relevance to white New Zealanders is as a universal settler story celebrating the struggles and spirit of the pioneers. This moves the narrative away from one of West Highland Gaelic or Scottish exceptionalism and exclusivity to one that has a wider settler appeal and which values co-operation and inclusivity. This is mirrored in the town’s Grand Pageant, a not insubstantial commitment for such a small community in terms of human and financial resources and one that in the new millennium has seen the inclusion of non-descendants as well as those of Nova Scotian descent. Despite the changes in messaging to align the story with the needs of contemporary society, there remains widespread engagement amongst the majority of the town’s Novies. Interviewing some of the community who participated in the 2013 pageant, including Novies, they largely echo Patsy Montgomery’s sentiments concerning the story.

It will be interesting to see how any future pageants deal with the settlers’ relationship with Māori, especially in light of the Museum’s Strategic Plan aspirations to

Develop a plan to increase engagement with the local community to ensure the Museum remains relevant to the growing and changing demographics of Bream Bay.

Allow for a changing exhibition – telling other dimensions of the story and our increasingly diverse community.76

Complicating these aims are the changing social and cultural demographics of New Zealand. For instance, the Scots-born only account for 0.6 per cent of the total 2013 population, whereas the most common birthplace for people living in New Zealand but born overseas was Asia with 7.9 per cent of the population born there. This represents a substantial contemporary immigration flow, when it is considered that only 11.8 per cent of New Zealand’s population identify themselves as ethnically Asian.77 In these circumstances the future relevance of an atypical Scottish migration is only likely to change. Reflecting on these changes and the migrant nature of New Zealand society, Patsy Montgomery notes that as Waipu is ‘the gateway to Northland … we could tell a whole range of migration stories and become a semi-migration museum.’78

The gaps in the history are evident and the omission of the story of the colonisation as it relates to Māori have still to be fully addressed and understood. This is a narrative that is still to be written, suggesting that the story will continue to evolve. Indeed, the cultural legacy of the Waipu migration is no longer that of the settlers, rather it is how the migration has been and continues to be repurposed by those that have followed, whether they be descendants or not. This says more about colonial identities and national identity creation in New Zealand than it does about West Highland Gaelic culture. Nor will this be surprising to migration historians, who will be well aware of how malleable migrant identities and memories can be and how they can even be refashioned in an individual migrant’s own lifetime, let alone by succeeding generations. The Waipu migration has been similarly readdressed and refashioned, aligning itself with the demands of contemporary New Zealand society and engaging with the changing attitudes and demographics of that society.

Notes

- “2013 Census,” Stats NZ – Tatauranga Aotearoa, updated 4 December 2020, https://www.stats.govt.nz/census/previous-censuses/2013-census/. ⮭

- “Waipu,” 100% Pure New Zealand, accessed 20 October 2021, https://www.newzealand.com/uk/waipu/. ⮭

- Brad Patterson, Tom Brooking and Jim McAloon with Rebecca Lenihan and Tanja Bueltmann, Unpacking the Kists: The Scots in New Zealand (Dunedin, 2013), 59. ⮭

- Marjory Harper, ‘Transplanted Identities: Remembering and Reinventing Scotland across the Diaspora’ in Tanja Bueltmann, Andrew Hinson and Graeme Morton (eds), Ties of Bluid, Kin and Countrie: Scottish Associational Culture in the Diaspora (Guelph, 2009) 21. ⮭

- Laurie Stanley, The Well-Watered Garden: The Presbyterian Church in Cape Breton, 1798–1860 (Sydney, Cape Breton, 1983), 150. ⮭

- Ibid., 156. ⮭

- Jock Phillips and Terry Hearn, Settler: New Zealand Immigrants from England, Ireland & Scotland, 1800–1945 (Auckland, 2008), 37; Michael Fry, The Scottish Empire (Edinburgh, 2001), 219. ⮭

- Gordon MacDonald, The Highlanders of Waipu or Echoes of 1745: A Scottish Odyssey (Dunedin, 1928), V. ⮭

- Stanley, The Well-Watered Garden, 157. ⮭

- Maureen Molloy, ‘McLeod, Norman – Biography’, The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (updated 1 September 2010), http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/1m39/1. ⮭

- T C Halliburton, An Historical and Statistical Account of Nova Scotia (2 vols: Halifax, 1829), I, 234. ⮭

- Norman McLeod, The Present Church of Scotland and a Tint of Normanism Contending in a Dialogue (Halifax, N.S., 1843). Quoted in Flora McPherson, Watchman against the World: The Remarkable Journey of Norman McLeod & his People from Scotland to Cape Breton Island to New Zealand (Wreck Cove, 1993), 23. ⮭

- Bev Brett, ‘Prologue’ in Bev Brett (ed.) John Alick MacPherson (trans), Letters to Mac-Talla from John Munro, A Cape Breton Gael in New Zealand 1894–1902 (Baddeck N.S., 2017), xv. ⮭

- Neil Robinson, To the Ends of the Earth: Norman McLeod and the Highlanders’ Migration to Nova Scotia and New Zealand (Auckland, 1997), 97. ⮭

- Norman McLeod to unnamed, 27 June 1849 in D. C. Harvey (ed.), ‘Letters of Rev. Norman McLeod 1835–1851’, Public Archives of Nova Scotia Bulletin, 2 (1939), 23. ⮭

- N. R. McKenzie, The Gael Fares Forth: The Romantic Story of Waipu and her Sister Settlements (2nd edition, Wellington, 1942), 34. ⮭

- Maureen Molloy, Those Who Speak to the Heart: The Nova Scotian Scots at Waipu 1854–1920 (Palmerston North, 1991), 34. ⮭

- McLeod, 27 June 1849 in Harvey, ‘Letters’, 24. ⮭

- Stanley, The Well-Watered Garden, 168. ⮭

- McPherson, Watchman against the World, 178. ⮭

- McLeod, 27 June 1849, in Harvey, ‘Letters’, 24–5. ⮭

- “Shipping List”, Daily Southern Cross, Volume X, Issue 650, 20 September 1853, Page 2. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DSC18530920.2.3?end_date=20-09-1853&query=Gazelle&snippet=true&start_date=20-09-1853&title=DSC. ⮭

- Molloy, Those Who Speak, 19. ⮭

- Ibid., 19. ⮭

- Stanley, The Well-Watered Garden, 150. ⮭

- See McKenzie, The Gael; Robinson, Ends of the Earth. ⮭

- Fry, The Scottish Empire, 220. ⮭

- Robinson, Lion of Scotland, 51. ⮭

- Ibid., 80. ⮭

- Molloy, Those Who Speak, 38. ⮭

- Ibid., 39. ⮭

- Tom Brooking, ‘Cargill, William’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1990, Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1c4/cargill-william (accessed 24 April 2022). ⮭

- A. H. McLintock, The History of Otago: The Origins and Growth of a Wakefield Class Settlement (Dunedin, 1949) 195. ⮭

- Rosalind McClean, ‘Scottish Piety: The Free Church Settlement of Otago, 1848–1853’ in J. Stenhouse and J. Thomson (eds) Building God’s Own Country – Historical Essays on Religions in New Zealand (Dunedin, 2004). ⮭

- ‘Canterbury Papers, London: Published for the Association for Founding the Settlement of Canterbury in New Zealand by John W. Parker, 1850’, Project Canterbury, http://anglicanhistory.org/nz/canterbury_papers1850.html (accessed 25 April 2022). ⮭

- Peter Boroughs, ‘Introduction’ in The Founders of Canterbury/edited by Edward Jerningham Wakefield; with a new introduction by Peter Burroughs (London, 1973), xxxii. ⮭

- Maureen Molloy, ‘“No Inclination to Mix with Strangers”: Marriage Patterns Among Highland Scots Migrants to Cape Breton and New Zealand, 1800–1916,’ Journal of Family History Vol.11 No.3 (1986) 231. ⮭

- ‘THE OUT-DISTRICTS. THE SOUTHERN CROSS’, Daily Southern Cross, 7 September 1858. paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/outdistricts-7Sep1858. ⮭

- Newspapers, Papers Past, accessed 4 December 2021. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers. ⮭

- MacDonald, The Highlanders, XXIII. ⮭

- Tamatekapua Law, ‘Brief of Evidence of Paraire Pirihi, WAI 1040, WAI 745, WAI 1308’, The Waitangi Tribunal, 4 October 2013. https://patuharakeke.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/public/website-downloads/Final-BOE-of-Paraire-Pirihi-1.pdf?vid=3. ⮭

- Malcolm McKinnon (ed.), Bateman New Zealand Historical Atlas: ko papatuanuku e takoto nei (Auckland, 1997), plate 11. ⮭

- MacDonald, The Highlanders, XVI. ⮭

- ‘Background to the Patuharakeke claim’, Bream Bay News, 22 May 2014, http://breambaynews.co.nz/pdf/22_5_14.pdf. ⮭

- See Letters 5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 17, 20, 28 and 32 in Brett (ed.), Letters to Mac-Talla. ⮭

- John Munro, ‘More about the Maori’ in Ibid., 29. ⮭

- ‘The Maoris’, The Grand Pageant; The Story of a Remarkable Migration; Waipu 2003 (Auckland: VidMac Films Ltd, 2003) DVD. ⮭

- ‘Early Settlement’, The Grand Pageant, DVD. ⮭

- T. Papps, ‘Growth and Distribution of Population’ in Population of New Zealand/Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific 12, 2 vols (New York, 1985), I, tables 8 and 17; Ian Pool, Te iwi Maori: A New Zealand Population, Past, Present & Projected (Auckland, 1991), 58. ⮭

- Alan Ward, ‘McLean, Donald’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1990, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (accessed 14 September 2021) https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1m38/mclean-donald. ⮭

- Superintendent of the Auckland Province, ‘Opening Address to the Auckland Provincial Council’, Journals of the Auckland Provincial Council, Session VIII (25 November 1857), 2. ⮭

- ‘Waitangi Tribunal created’, Ministry for Culture and Heritage (updated 8 October 2021). https://nzhistory.govt.nz/waitangi-tribunal-created. ⮭

- Patsy Montgomery, Interview by Iain Watson, Waipu, New Zealand, held at The School of Scottish Studies Sound Archive, University of Edinburgh, 10 December 2014. ⮭

- Waipu Centennial Trust Board Strategic Plan, ‘About Us – Strategic Plan 2021,’ Waipu Museum, https://www.waipumuseum.com/museum/about-us/. ⮭

- ‘AUCKLAND WEEKLY NEWS’, New Zealand Herald, 18 February 1903, 5. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19030218.2.38?end_date=01-03-1903&items_per_page=10&page=2&query=Waipu+Jubilee&snippet=true&sort_by=byDA&start_date=01-12-1902&type=ARTICLE. ⮭

- Molloy, Those Who Speak, 74. ⮭

- Genesis, 12:1, KJV. ⮭

- Ecclesiastes, 12:1, KJV. ⮭

- ‘Waipū Caledonian Society Roll of Honour’, NZ History, Ministry for Culture and Heritage. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/waip%C5%AB-caledonian-society-roll-honour (updated 14 April 2022). ⮭

- MacDonald, The Highlanders, XXII. ⮭

- ‘Results of the Census of the Dominion of New Zealand, taken for the night of the 2nd April 1911,’ Statistics New Zealand Tatauranga Aotearoa. https://www3.stats.govt.nz/historic_publications/1911-census/1911-results-census.html. ⮭

- Patsy Montgomery, Interview by Iain Watson, 11 January 2013, Waipu, New Zealand, held at The School of Scottish Studies Sound Archive, University of Edinburgh. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- Sandra Bogart, ‘Photographic Memory put to use Cataloguing Local History’, The Northern Advocate, 2 January 2012, http://www.nzherald.co.nz/northern-advocate/news/article.cfm?c_id=1503450&objectid=11050476. ⮭

- Montgomery, 2014 interview. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- Waipu the Search for Paradise, directed by John and Karen Bates, narrated by Peter Elliott and letters read by Robert Bruce (Auckland, 1999) Video Cassette. ⮭

- Montgomery, 2014 interview. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- Tanja Bueltmann, Scottish Ethnicity and the Making of New Zealand Society, 1850–1930 (Edinburgh, 2011), 5. ⮭

- MacDonald, The Highlanders, chap. IV; McKenzie, The Gael, 206. ⮭

- John Wilson, ‘Scots’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/scots (updated 25 March 2015). ⮭

- See Rosalind McClean, Scottish Emigrants to New Zealand 1840–1880: Motives, Means and Background, Ph.D. dissertation (University of Edinburgh, 1990); Jeanette M. Brock, The Mobile Scot: Emigration and Migration, 1861–1911 (Edinburgh, 1999). ⮭

- James Belich, Making Peoples: A History of the New Zealanders – From Polynesian Settlement to the End of the Nineteenth Century (Auckland, 1996), 315. ⮭

- Bueltmann, Scottish Ethnicity, 5. ⮭

- Waipu Strategic Plan. ⮭

- ‘2013 QuickStats About Culture and Identity,’ Statistics New Zealand (2014), 2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity, https://www.stats.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Retirement-of-archive-website-project-files/Reports/2013-Census-QuickStats-about-culture-and-identity/quickstats-culture-identity.pdf. ⮭

- Patsy Montgomery, 2014 interview. ⮭

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Author Information

Iain Watson, a member of the Scottish Diaspora, was born in Singapore, and raised in Southeast Asia. He has had a 29-year career as a banker sojourning internationally with lengthier assignments in France, the Yemen, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Australia, and the City of London. He left the financial services industry in 2006 and holds a BA Hons in History from the Open University, an MSc in Diaspora and Migration History and a PhD in History from the University of Edinburgh where he now works in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology. His historical interests are the End of the European Empires, Post-Colonialism and Contemporary Migration and to support his research, uses and collects oral testimonies. He is currently working on a book, commissioned by Edinburgh University Press, comparing Scottish settler migration to New Zealand with Scottish sojourner migration to Hong Kong since 1950, as part of a series of books on Scottish migration.